In the vast expanse of space, where the boundaries of our solar system blur into the cosmic unknown, a rare guest has arrived. Dubbed 3I/ATLAS, this interstellar comet is hurtling toward the Sun on a path that defies the gravitational pull of our star system. Discovered just months ago, it's not an asteroid but a comet—a frozen relic from another stellar neighborhood—now making its closest pass near Earth. As of today, the object is brightening rapidly, offering astronomers a fleeting window to unravel its secrets before it slingshots back into the void.

A Serendipitous Discovery

The story of 3I/ATLAS begins on July 1, 2025, when the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS)—a NASA-funded network of telescopes designed to spot potentially hazardous rocks—captured its faint glow. Located at the ATLAS station in Río Hurtado, Chile, the survey initially flagged the object as a possible near-Earth asteroid under the temporary designation A11pl3Z. Early data hinted at a highly eccentric orbit that might skim perilously close to our planet, prompting its brief listing on the International Astronomical Union's Near-Earth Object Confirmation Page.

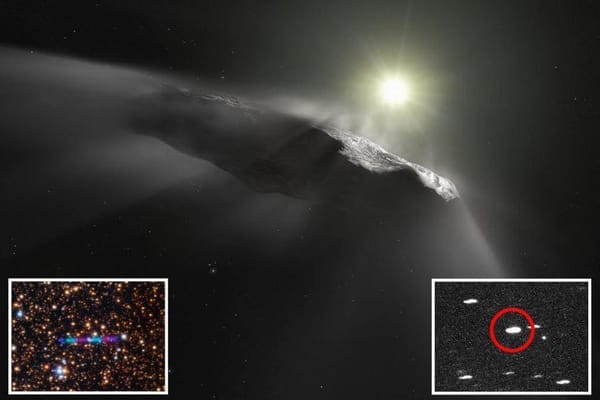

But follow-up observations from observatories worldwide quickly painted a different picture. The object's trajectory revealed a hyperbolic path—an unbound orbit escaping the Sun's gravity—with an excess velocity of about 58 km/s (36 mi/s). This confirmed what astronomers had hoped for: 3I/ATLAS is the third confirmed interstellar object (ISO) to visit our solar system, following 1I/'Oumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019. Pre-discovery images from ATLAS telescopes dating back to late June 2025 suggest it was lurking near the dense star fields of the Galactic Center, making it tricky to spot earlier.

At discovery, 3I/ATLAS was 4.5 AU (about 670 million km or 420 million miles) from the Sun, nestled within Jupiter's orbit and roughly 3.5 AU (524 million km or 325 million miles) from Earth. Originating from the direction of Sagittarius, near the Milky Way's core, this "fun space rock," as one astronomer called it, is a time capsule from a distant star system, ejected perhaps billions of years ago by gravitational tussles with planets or other stars.

Not an Asteroid, But a Comet with a Twist

Initial confusion arose because 3I/ATLAS appeared asteroid-like: a faint, fast-moving dot without obvious cometary features. But as it drew closer to the Sun's warmth, activity bloomed. Spectroscopic data revealed a coma—a hazy envelope of gas and dust—dominated by large, micrometer-sized grains with a reddish hue, akin to D-type asteroids or the interstellar comet Borisov. This coloration likely stems from irradiated organics like tholins, organic polymers formed by cosmic radiation.

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope provided the sharpest view yet on July 21, 2025, when the comet was 277 million miles (446 million km) from Earth. The image showed a teardrop-shaped dust cocoon trailing from its icy nucleus, confirming its cometary nature. Size estimates vary: Hubble suggests a nucleus up to 3.5 miles (5.6 km) across, while Harvard's Avi Loeb posits it could exceed 3.1 miles in diameter, weighing over 33 billion tons—making it the largest known interstellar visitor.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) chimed in on August 6, 2025, using its Near-Infrared Spectrograph to detect an unexpectedly high abundance of carbon dioxide in the coma, alongside water ice in the nucleus. This CO₂ richness hints at the comet's birthplace: perhaps beyond the CO₂ ice line in its parent protoplanetary disk, where temperatures allowed such ices to form stably. "Studying 3I/ATLAS helps us peek at the chemistry of other star systems during their formative years," notes a JWST team preprint. Compared to our solar system's birth 4.6 billion years ago, this could reveal how diverse planetary building blocks truly are.

Trajectory: A Safe Flyby Near Earth

Though ATLAS's name evokes planetary defense, 3I/ATLAS poses zero threat. Its hyperbolic path will carry it to perihelion—closest to the Sun—on October 30, 2025, at 1.4 AU (210 million km or 130 million miles), just inside Mars' orbit. Before that, it will buzz Mars on October 3 at a tantalizing distance, observable by ESA's Mars Express, ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, and NASA's fleet.

Earth's closest encounter comes in December 2025, at a safe 1.8 AU (270 million km or 170 million miles)—over 1.5 times the Earth-Sun distance, and on the Sun's far side, briefly hiding it from view. By then, the comet will be visible again post-sunset in equatorial skies, peaking at magnitude 12–13, requiring an 8–12 inch telescope for backyard observers. It will exit the inner solar system by early 2026, fading into interstellar space.

No mission can catch it—its speed demands a delta-v of 7 km/s from Earth or 5 km/s from Mars—but future concepts like ESA's Comet Interceptor could target the next ISO.

Why This Matters: Echoes of Alien Worlds

Interstellar objects like 3I/ATLAS are the galaxy's nomads, with estimates suggesting seven pass within 1 AU of the Sun annually. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory's upcoming Legacy Survey of Space and Time could spot dozens more, revolutionizing our understanding of extrasolar systems. Is 3I/ATLAS the "oldest comet we've ever seen," packed with pre-solar water ice? Or, as fringe theories whisper (including a controversial paper by Avi Loeb questioning if it's "possibly hostile" alien tech), something engineered? Mainstream science dismisses the latter as "nonsense"—it's a natural icy wanderer.

As 3I/ATLAS nears its solar rendezvous, it reminds us: our solar system is no isolated bubble. It's a bustling highway for cosmic travelers, each carrying whispers from stars we'll never visit. For now, telescopes worldwide are locked on this third interstellar envoy, hungry for every last datum before it bids farewell. In a universe of 100 billion stars, we're not alone in the traffic—we're just starting to notice the passersby.